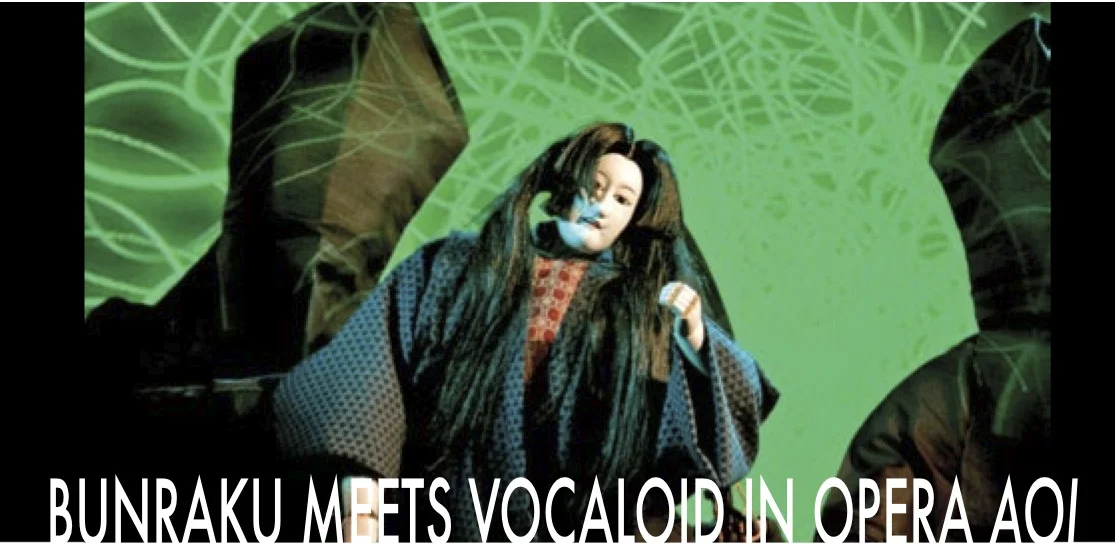

Recently, bunraku puppets have been appearing in a variety of new collaborations that extend beyond the traditional bunraku framework. In 2002, Sonezaki-Shinjū Rock took Chikamatsu Mon- zaemon's 1703 classic The Love Suicides at Sonezaki and set it to a new rock music score. The band performed in the background as the puppets took center stage in traditional costumes under rock concert lights. In 2011, visual artist Hiroshi Sugimoto adapted the same play with a contemporary design aesthetic, digital projections, and a restored prologue with newly composed music. Opera Aoi, which premiered at Hyper Japan in London in 2014, represents the most radical departure yet. The opera, which was conceived as a film rather than a live performance, is scored with techno music and vocaloid singing in place of the three-stringed shamisen and the vocal work of the chanter. The world of film and vocaloid is so different from traditional bunraku that puppeteer Yoshida Kōsuke said it was "as if a bunraku puppeteer has landed on the moon."2

The film's blending of multiple traditional elements drawn from noh drama and bunraku with the contemporary technology of film, digitized music, and vocaloid software ultimately suggests that the future of the traditional arts lies in making them relevant to contemporary audiences through their integration with new forms.

The source for the opera comes from an early noh play, Lady Aoi, which in turn drew from the classical literary masterpiece, The Tale of Genji. Both in the noh play and the original, the story centers around the jealousy Genji's mistress, Rokujō, feels toward his wife, Aoi. In her jealousy, Rokujō's spirit possesses Aoi, which makes her dangerously sick and, in the original, causes her death. In Opera Aoi, the creator, Hiroshi Tamawari, adapts the slighted mistress into a forgotten artistic muse, Midori. Midori, the vocaloid software, becomes obsolete without the composer who transformed her library of sounds into music. In her jealousy, she, too, possesses Aoi at the climax of the story.

This central theme, the importance of the human being who uses the vocaloid technology to create expression and meaning, is underscored by how Opera Aoi films the puppetry. First, the film emphasizes the object-ness of the puppets. The first shot of a puppet in the film opens with a long shot. Aoi's manager sleeps. The natural pose and the distance of the camera make it difficult to distinguish that the sleeping figure is indeed a puppet. Then the film cuts to a close up of the puppet's polished wooden foot. The camera slowly pans across the puppet to reveal the gaps at the finger joints that allow the fingers of the puppet to move and the black-clad figure of the lead puppeteer. The stillness of the object further emphasizes that it is a puppet. The puppet does not begin to appear lifelike until the puppeteer raises its head a few moments later. In this way, the film highlights that the true creator of the life and emotions of puppet is the puppeteer.

Additionally, the camera generally frames the puppets to include the presence of the puppeteer. Three puppeteers operate the puppet for Aoi: one for the feet, one for the left arm, and the lead puppeteer for the head and right arm. The other two characters, Aoi's manager and the psychiatrist, are both operated by a single puppeteer. The puppeteers wear black and cover their faces in hoods, but their presence behind the puppets and their movements as they manipulate the puppets are a visual presence throughout the film.

In traditional bunraku, the puppeteers are not the only artists who bring emotion to the puppets. The chanter, who recites descriptive passages, portrays all the characters in the dialogue, and sings the lyrical passages, is a critical element in conveying the emotions of the characters. For this reason, replacing the chanter with a vocaloid raises one of the biggest questions of the film: Will the vocaloid be able to capture the range of human emotions to give the story emotional weight? Voice actor Ishiguro Chihiro and vocaloid producer EHAMIC created the vocaloid for Opera Aoi, Yuzuki Yukari, specifically for the film. Vocaloid software, which manipulates a library of sounds created by a human voice, debuted in 2000. The process of creating the library of sounds takes about 100 hours.3 Vocaloid, most commonly associated with pop music and anime, intersected with bunraku in 2008 when vocaloid pop icon Hatsune Miku sang a musical adaptation of The Love Suicides at Sonezaki as a techno pop song. While the juxtapostion of the vocaloid with source material originally created for puppets posed interesting questions about the similarities between vocaloid and puppets, Opera Aoi takes the vocaloid/puppet interaction to a new level by using a vocaloid to bring emotional life to puppets.

The vocaloid lacks the raw emotion and human timbre of the unaltered human voice of the chanter. But the range of the vocaloid captures the core emotions of the characters, and the technology allows for a layering of voices that a human voice cannot produce. In the dialogue sections, the vocaloid lines overlay on each other to build momentum within the scene. EHAMIC also layers the vocaloid sounds to create two separate musical sounds. For example, he pairs the sung narration with the melody of one of Midori's hit songs, which was based on a Buddhist mantra. This juxtaposes melody, rhythm, and style and adds musical complexity to the piece.

Ultimately, bunraku is the star of Opera Aoi. At the climax of the film, Midori possesses Aoi, who is hospitalized. Aoi's movements become less human and more like a doll being animated by an external force. Her hands hang limp at her sides. Her head falls forward then straightens only to fall forward again. Then her back arches slightly and, when she bends forward, her face transforms. The puppeteers use a gabu puppet head, which opens at the eyes and mouth. The eye sockets appear to deepen. The mouth changes from a closed, petite, elegant mouth to a wide grimace. As Aoi's manager and the psychiatrist attempt to placate Midori's vengeful spirit, Aoi's face continues to transform from a beautiful woman to a demon in succession until Aoi collapses. When she comes to, she will have no memory of the spirit possession.

By focusing on the physical puppet, the puppeteers, and the expressive possibilities of the bunraku puppetry, as showcased in the use of the gabu head, Opera Aoi affirms bunraku as an amazing art form worthy of our attention. The use of film and vocaloid technology also demonstrates that the traditional puppetry has artistic potential outside the usual parameters. The vocaloid's challenge to the chanter opens possibilities for new experiments that take the puppet beyond the bunraku context. Additionally, film can travel more easily than a live performance and opens new possible audiences. Similarly, vocaloid fans represent a hitherto untapped potential audience. Opera Aoi suggests that these technologies, whether the centuries old bunraku or the 21st century vocaloid, need a human element to be expressive. It also opens new pathways for audience development to make bunraku culturally relevant to a new generation.

Jyana S. Browne is a PhD candidate at the University of Washington. She recently spent two years in Japan researching love suicide plays in the 18th-century puppet theatre.

Endnotes

1 Opera Aoi. Dir. Kano Shin. Perf. Yoshida Kōsuke, Yoshida Kanichi, Kiritake Monhide. Star Gate Co. Ltd., 2014. Film.

2 The Vocaloid Opera Aoi with Bunraku Puppets. Press Release. Opera Aoi, 2014. Print.

3 Josiah. "Hyper Japan 2014: Vocaloid Opera Aoi with Bunraku Puppets Interview." Parallax Play. 7 Aug. 2014. Web. 2 Nov. 2014.